How Do You Define Color?

The library at our office is no stranger to unique volumes with storied histories going far beyond their pages. One such title is the ISCC-NBS Method of Designating Colors and a Dictionary of Color Names. Issued in 1955 by the U.S. Department of Commerce National Bureau of Standards, the book is a time capsule in and of itself, transporting us to the mindset of post-war America, at once so efficient and neurotic that it created a standard system for classifying colors.

First, The ISCC-NBS Method Itself

The purpose of the dictionary and its methodology is to define color vocabulary for the scientist, the businessman, the layman. The book describes the vital importance of color naming semantics, stating that when naming colors used in pigments and dyes, names often refer to geographic location and evoke a deep sense of place-making, wonder and exoticism; when naming colors used in retail, best practice calls for words that “explore the beauties and wiles of the fair sex” and yet still other names are best made fanciful and in vogue, intended for the writer and silvertongued of us all. Of these color titles, the book taunts, “Do not suppose that these names are without economic importance.”

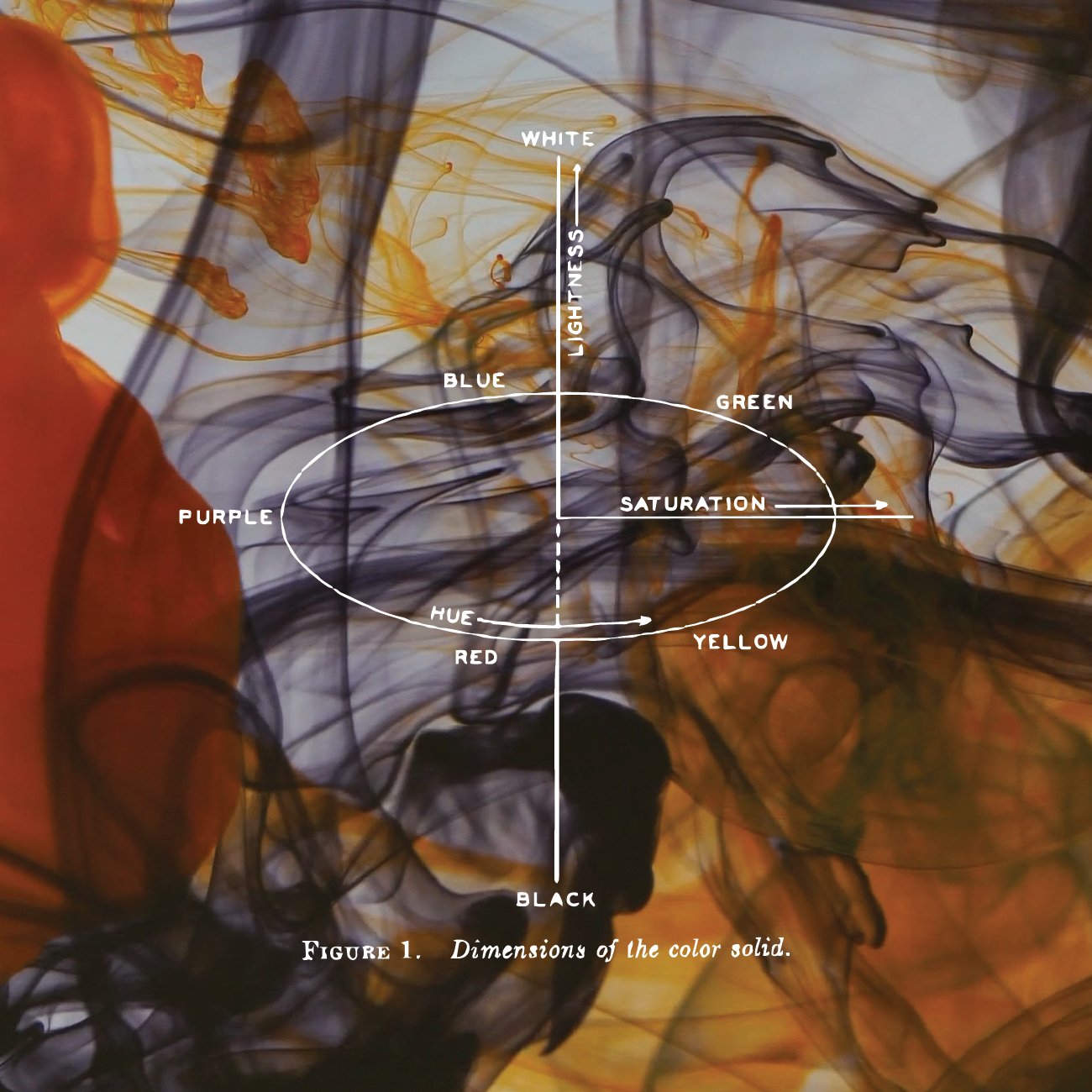

Going beyond cataloguing color names created by six companies with different industry backgrounds (and therefore approaches to naming semantics), the book also outlines the process of naming new colors. That task is as simple as referencing a Munsell chart, which looks as above. The x-axis, Munsell Chroma, refers to saturation, while the y-axis, Munsell Value, refers to lightness. Modifiers within the chart are then tacked onto the origin color to create a comprehensive, all-encompassing and very descriptive name, such as grayish reddish brown.

The ISCC-NBS Method in Context

The book and its standards were published at a time when America was recovering from World War II. The post-war boom gave way to a period of prosperity, marked by the Cold War, the Space Race and industries expanding with the introduction of new technology such as the jet aircraft, transistor and computer. At that time, America was obsessed with efficiency and order, and the National Bureau of Standardsprovided the standards and science necessary to enable the U.S.’s economic and political competitiveness. To this day, NIST still promotes U.S. innovation and industrial competitiveness by advancing measurement science, standards and technology in ways that enhance economic security and improve our quality of life.

Why This Method Matters

Nowadays, science has determined that people don’t see color the same. Color is determined by the wavelength of light reflecting on an object, but how our brain processes that wavelength and translates it visually can vary. It can be slippery, and even disturbing, to consider that your blue may not be the same blue as someone else’s, even if they share the same name and wavelength.

In the face of uncertain times, there’s actually something comforting about the methodical and comically mundane process of defining colors outlined in the book. A true testament to the control asserted in the scientific process, the book went so far as to define “recommended conditions of lighting and viewing,” or, simply put, “the ordinaryviewing conditions.”

Those conditions are as follows:

A table placed by a window so that light reaches the table top from the operator’s left or right chiefly from the sky and chiefly at angles centering on 45 degrees from the horizontal is recommended. A north window is best because no special precautions are usually required to eliminate direct sunlight. A canopy of black cloth, preferably black velvet, should be hung above the sample on the side opposite the operator in such a position as to be imaged in the mirror surface of the cover glass; such an arrangement eliminates errors from unwanted admixture of ceiling light reflected from the cover glass.

The procedure is so precise as to feel performative, reaching a near Maggie Nelson a la Bluetslevel of glorifying color. Because of its depth, the indulgence of this efficiency promotes productivity, but promotes, too, a peculiar level of romanticism and artistry.

Seeing Things Differently

At Otherwise, we see things differently, from lectures attended outside of work given by famous literary figures, to old tomes pulled from the bookshelf. We’re drawn to these unusual ideas, and continue to examine them past initial contact, because we’re interested in the intricacies of pattern-making, of how humans seek to create meaning in this world.

In the case of the ISCC-NBS, science becomes one way of processing the every day, taking methodical care to catalogue and process that which surrounds us. There is a poetry in methodology — it’s an analogy that keeps coming back. One person may think that to stop, smell the roses and truly appreciate the beauty of that moment, you must see a rose as nothing other than a rose. But to us, it’s worthwhile not only to stop and smell the rose, but to know what makes the rose smell as it does, to know why we react to that experience so strongly. The experience doesn’t lose its meaning just because we broke it down to its smallest molecule — in fact, that probing understanding only deepens our joy in the experience. In that way, science becomes poetry, the methodical becomes the romantic, and in blurring those lines, we learn how to blur the lines in other realms of thinking. We discover overlap and intersections, discover coincidences, discover surprising juxtapositions that create deeper angles and corners.