Fritz Pollard, An All-American Legacy

Every Black History Month, the country tends to celebrate the same manifold of historical figures. They are the civil rights leaders and abolitionists whose faces we see on calendars and postage stamps. These figures resurface each February when we commemorate African-Americans who have transformed America and quite frankly, they deserve all of their accolades, and then some. But we’d like to take the time to highlight those who have been otherwise—invisible.

As sports became a growing national obsession, football — which emerged from a bout of friendly collegiate competition — seemed to hold the door open, at least a crack, for Black athletes.The most ardent of football fans probably have heard of the likes of Kenny Washington and Art Shell. Washington broke through the color barrier in the “modern NFL” era in 1961 and Shell was the first African-American coach in the league, taking the helm at the Oakland Raiders in 1989. But when speaking about “firsts” for Black professionals in American football, you shouldn’t go another day without knowing the name Fritz Pollard, and appreciating the changes he was able to usher in for the game.

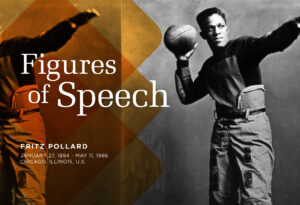

Frederick Douglass Pollard was born in the Rogers Park neighborhood of Chicago in 1894, which was a largely German-immigrant community at the time. That’s where he received the nickname Fritz. His father was a former champion boxer and barber during the Civil War and his mother was a Native American seamstress.

Fritz was small, even for the days of early football, but he had grit in his veins. He was the first African-American to be selected for the Cook County All-Star team which gave him the opportunity to play for Brown University in the Ivy League. Today, teams like Brown, Yale and Harvard may not be the big-wigs of college football, but in their time, they had the reputations akin to those held by teams like USC, Alabama and Florida today. Also, did we fail to mention that they were basically all white? So for a Black man like Pollard to run circles around Yale, it attracted a lot of attention, for better, and for worse.

Pollard was also the first African-American to be selected to the Walter Camp All-America team in 1915. That season, Brown went 5-3-1, but was chosen to play Washington State in the Rose Bowl after Syracuse bowed out. With this turn of events, Pollard became the first African-American to play in the Rose Bowl. Consequently, because of the color of skin, he was refused service by the porters of the Pullman train car that carried his team across the country. Even the hotel in Pasadena where the rest of the team was housed refused to give Pollard a room. Until, that is, his coach threatened to remove the entire Brown team, which caused the hotel management to acquiesce and let him stay.

In spite of Brown’s devastating loss at the Rose Bowl, Fritz finished his time at Brown on the football roster. He later studied to become a dentist at the University of Pennsylvania and served in the army during World War I. It was after he returned, however, that he was recruited to play football professionally. Playing with the Akron Pros of the American Professional Football League (which later would become the NFL), as you can expect, he was the target of taunts from fans and malicious attacks from the players on other teams. What did Pollard do? “I didn’t get mad at them and want to fight them. I’d just look at them and grin, and in the next minute run for an 80-yard touchdown,” Fritz told NFL Films.

It’s not bragging, if you can back it up. And back-it-up Pollard did more often than not. The Pros went 8-0-3, winning the league’s first title in 1920. But there seemed to be something more important to football than just playing the game for Fritz. He wanted the honor of being the first Black coach more than anything else, and the following year, his dream would come true. He launched a stellar coaching career in 1921 by leading the Akron Pros; later he coached the Milwaukee Badgers (1922), the Hammond Pros (1923, 1925) and the Providence Steam Roller (1925). In 1928, Fritz Pollard created an all African-American football team, the Chicago Black Hawks, that went trailblazing through the West Coast, leaving other teams during the Great Depression (especially those that patronized the Black Hawks), in the dust.

Pollard went on to found the first Black tabloid in 1935, Independent News, along with the first Black investment firm and would go on to be an agent representing Black entertainers in Hollywood. Fritz Pollard died at 92, on May 11, 1986, but lived more than one lifetime when he was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame a little less than three decades later, in 2005.

If there is one thing we can take from Pollard, it’s that legacy takes many forms. Oftentimes, it’s something felt rather than documented, but there are times, such as today, when its ripples can be seen and its reverberations felt — and will be long after we are gone. Fritz Pollard was more than a football player with grit in his veins, he was a true and great leader.