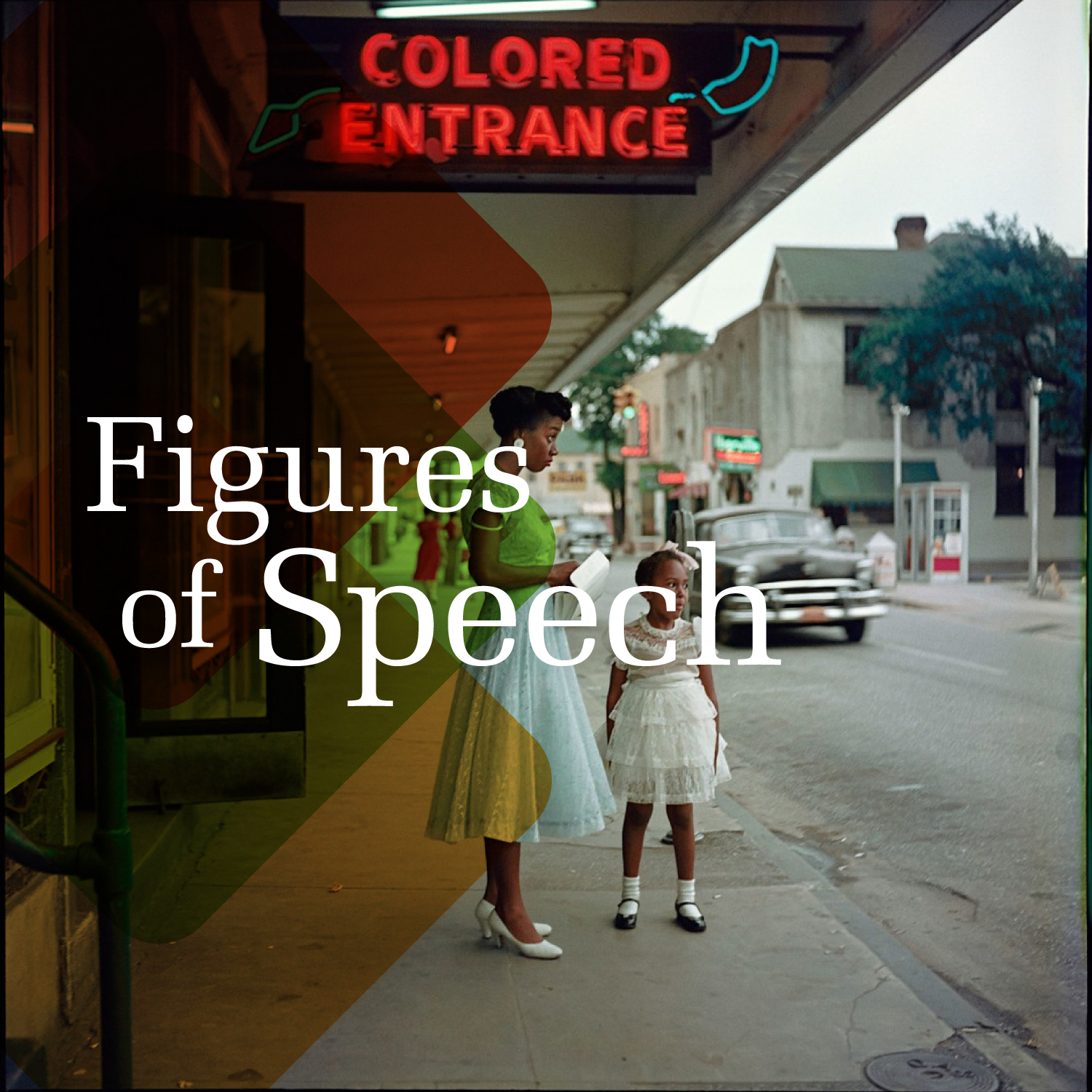

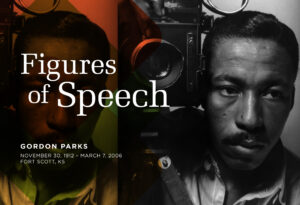

Figures of Speech: Gordon Parks

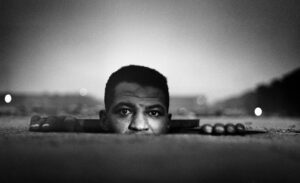

“I saw that the camera could be a weapon against poverty, against racism, against all sorts of social wrongs. I knew at that point I had to have a camera.”

There is perhaps no individual who conveys the power and prose of photography more than Gordon Parks. One of the iconic photographers of the twentieth century, Parks was born into poverty and segregation in Fort Scott, Kansas, in 1912. From an early age, he was drawn to photography when he saw images of migrant workers taken by Farm Security Administration (FSA) photographers in a magazine.

Shortly after discovering the field of photography, he bought himself a camera from a pawnshop, and taught himself how to use it. The first decade of his career was spent capturing the awe and stature of Chicago socialite Marva Louis, the spirituality of churchgoers in Washington D.C. and portraits of prominent figures at the time including Richard Wright and Marian Anderson. Despite his lack of professional training, Parks flourished in the world of photography, earning the Julius Rosenwald Fellowship in 1942 because of the unique way he saw and interacted with beauty within African-American culture.

In the face of racial injustice and inequity, Gordon fought back using his weapon of choice — the camera. His unique way of wielding the camera would later illuminate issues of poverty, violence and oppression that defined much of the decade between 1940 and 1950. In the midst of World War II, with the American military still segregated, Parks was able to make a bold statement about the disparities between the promise and realities of the American Dream through photographs like Washington, D.C., Government charwoman (American Gothic).

Parks also freelanced for Glamour and Ebony, which expanded his photographic practice and further developed his distinct style. His 1948 photo essay on the life of a Harlem gang leader won widespread acclaim and earned Parks a position as the first African-American staff photographer for Life. He remained at Life magazine for two decades, covering subjects ranging from racism and poverty to fashion and entertainment, taking memorable pictures of prominent figures such as Muhammad Ali, Malcolm X, Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. and Stokely Carmichael.

Many argue that Gordon Parks was a modern-day Renaissance man, whose creative practice extended far beyond the lens to encompass fiction and nonfiction writing, musical composition, filmmaking and painting. In 1969, he became the first African-American to write and direct a major Hollywood studio feature film, The Learning Tree and then Shaft in 1971, that inspired many sequels. And yes, both were box office successes. The last 30 years of his life were spent evolving his style, and he continued working until his death in 2006.

Parks was recognized with more than 50 honorary doctorates, and among his numerous awards was the National Medal of Arts, which he received in 1988. Today, archives of his work are held at a number of institutions including the Gordon Parks Foundation (Pleasantville, NY); the Gordon Parks Museum (Fort Scott, KS), Wichita State University, the Library of Congress, the National Archives and the Smithsonian Institution.