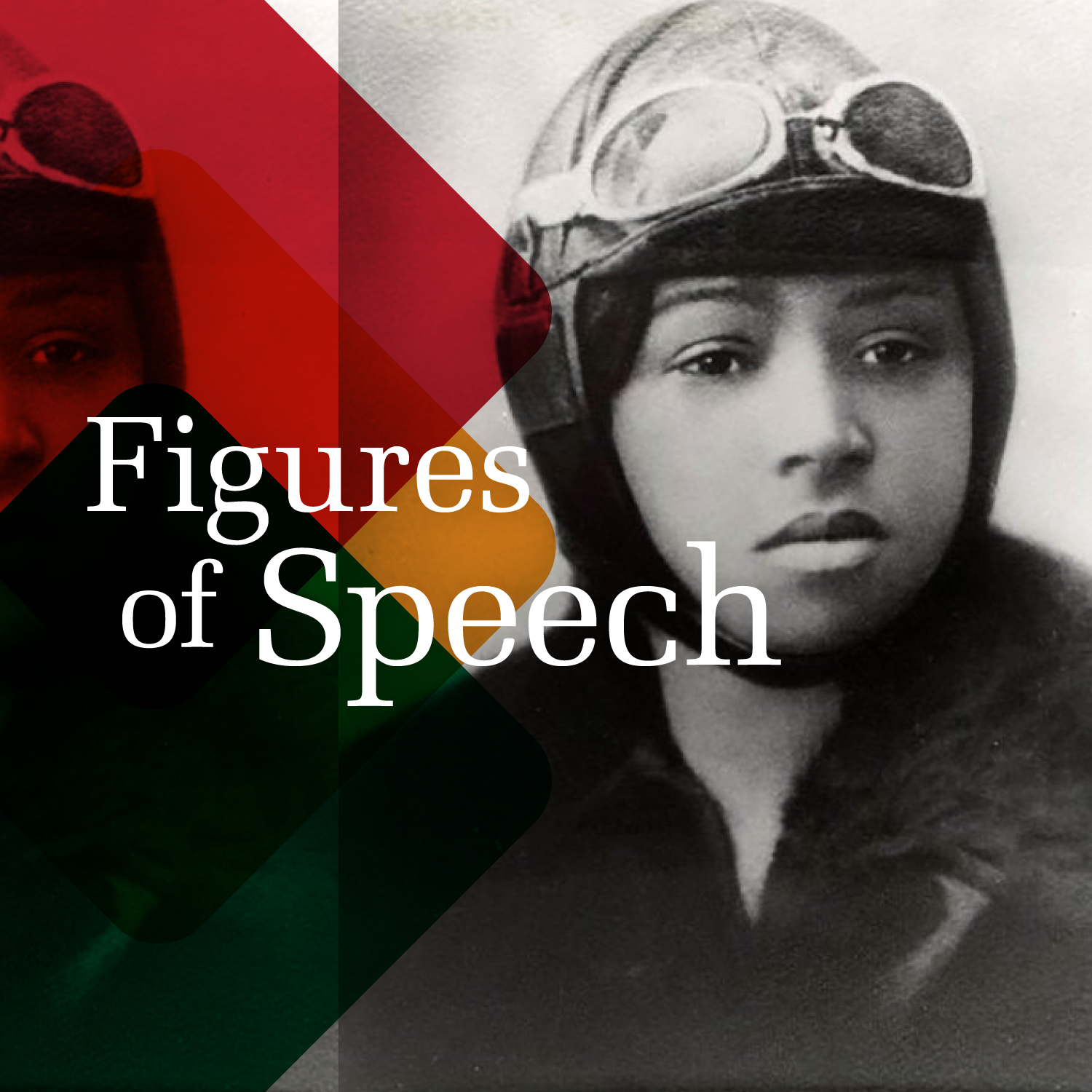

Figures of Speech: Bessie Coleman

Every year, the country tends to celebrate the same historical figures.They are the civil rights leaders, abolitionists and contributors to society whose faces we see on calendars and postage stamps. These same figures resurface annually when we commemorate those who have transformed America and quite frankly, they deserve all of their accolades, and then some. But in light of Women’s History Month, we’d like to take the time to highlight women whose inspiring contributions have been otherwise-invisible.

“Brave Bessie,” “Queen Bess,” and “The Only Race Aviatrix in the World.” These were all nicknames given to Bessie Coleman, the first woman of African-American and Native-American descent to soar brilliantly across the sky as a pilot — only 20 years after the invention of the first airplane. Known for her grit, and ambition, she was one of the meanest pilots to ever touch a yoke, performing a variety of tricks throughout her incredible, but heartbreakingly short-lived career, when her life was cut short in a tragic plane crash. Her goal was to encourage women and African-Americans to reach for their dreams, the same way she reached for the sky.

Coleman was born in Atlanta, Texas on January 26, 1892. Her mother, who worked as a maid, was African-American, and her father was a sharecropper of mixed Native American and African-American descent. Coleman grew up in a household with twelve brothers and sisters. In 1901, her father decided to move back to Oklahoma to escape discrimination, but Coleman, her siblings, and her mother, chose to stay in Texas. Through picking cotton and washing laundry, Coleman saved enough money by the age of 18 to attend the Colored Agricultural and Normal University (now Langston University) in Langston, Oklahoma.

At 23, she moved to Chicago to live with her brothers, attending Burnham School of Beauty Culture in 1915 and later became a manicurist in a local barbershop. Her brothers served in the military during World War I and came home telling stories of their time in France. Her brother, John, teased her about French women being able to fly airplanes, and at a time when women pilots were practically unheard of — within the United States — this was all but a pipe dream for someone like Bessie Coleman, or was it?

The stories her brothers told inspired her to take matters into her own hands. At the very least, she wanted to make an impact. What Coleman really aimed for was to have her take-off heard around the world. She applied to numerous flight schools across the country, but faced endless rejection because of her race and gender. Through the guidance of the first African-American newspaper publisher, Robert Abbot, Coleman turned her energies to France, where she was accepted at the Cauldron Brothers’ School of Aviation in Le Crotoy. It was on June 15, 1921 when she would receive her international pilot’s license from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale — becoming the first woman of African-American and Native American descent to earn her pilot license.

Coleman’s dream was to own a plane and to open her own flight school. She gave speeches and showed films of her aerial tricks at churches, theaters, and schools to earn money. She refused to speak anywhere that was segregated or discriminated against African-Americans. In 1922, she performed the first public flight by an African-American woman. She was famous for her thrilling “loop-the-loops” and “figure 8s” in an airplane. People were intrigued by her performances, and she became more popular in the United States and in Europe. She toured the country giving flight lessons and performing in flight shows, and she encouraged African- Americans and women to learn how to fly.

Only two years into her flight career, Coleman survived her first major plane accident. In February 1923, her airplane engine suddenly stopped working mid-flight and crashed. She suffered a broken leg, several cracked ribs, and numerous cuts on her face, but Coleman was unphased. Coleman returned to performing dangerous air tricks in 1925, and her determination helped her to purchase her own plane, a Jenny – JN-4 with an OX-5 engine.

Coleman returned to her hometown in Texas to perform for a large crowd. Texas was segregated at the time. The managers planned to create two separate entrances for African-Americans and white people to get into the stadium. “Brave Bessie” refused to perform unless there was only one gate for everyone to use. After many meetings, the managers agreed to have one gate, but people would still have to sit in segregated sections of the stadium. She ultimately agreed to perform and became famous for publicly standing up for her beliefs.

It would only be three years after her first accident that her life would come to a tragic end in another plane crash, alongside William Will (her mechanic). In 1926, Wills piloted the plane while Coleman sat in the passenger seat. At 3,000 feet in the air, a loose wrench got stuck in the engine of the aircraft and with Wills no longer in control of the steering wheel, the plane barrelled over, causing Coleman to fall out of the plane — Wills crashed the aircraft just a few feet away and died as a result.

In 1931, the Challenger Pilots’ Association of Chicago started a tradition of flying over Coleman’s grave every year. Many aviation clubs were named in her honor, including the Bessie Coleman Aero Club, organized by William Powell in the 1930s, and the Bessie Coleman Aviators, which began in Chicago in 1977. In 1990, the main road at O’ Hare International Airport was named Bessie Coleman Drive. Only five years later, the “Bessie Coleman Stamp” was issued to commemorate all of her accomplishments. In 2023, the U.S. Mint released a special quarter featuring Bessie Coleman as part of the American Women Quarters™ Program.

Her legacy continues to inspire communities all over the country and there are perhaps no accolades that could describe the effect she had on the world. Yet nicknames such as, “Brave Bessie,” and “Queen Bess” continue to serve as monikers almost 100 years later for Bessie Coleman, whose take-off can still be heard around the world.